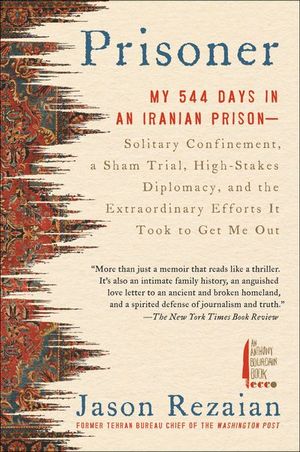

Prisoner

An Iranian American journalist recounts his headline-making captivity in Tehran in “a memoir that reads like a thriller” (The New York Times Book Review).

In July 2014, Washington Post Tehran bureau chief Jason Rezaian was arrested by Iranian police, accused of spying for America. The charges were absurd. Rezaian’s reporting was a mix of human interest stories and political analysis. He had even served as a guide for Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown. Initially, Rezaian thought the whole thing was a terrible misunderstanding, but things grew dire as it became an eighteen-month prison stint with impossibly high diplomatic stakes.

Rezaian had tireless advocates working on his behalf. His brother lobbied political heavyweights including John Kerry and Barack Obama and started a social media campaign—#FreeJason—while Jason’s wife navigated the red tape of the Iranian security apparatus, all while the courts used Rezaian as a bargaining chip in negotiations for the Iran nuclear deal.

In Prisoner, Rezaian writes of his exhausting interrogations and farcical trial. He also reflects on his idyllic childhood in Northern California and his bond with his Iranian father, a rug merchant; how his teacher Christopher Hitchens inspired him to pursue journalism; and his life-changing decision to move to Tehran, where his career took off and he met his wife. Written with wit, humor, and grace, Prisoner brings to life a fascinating, maddening culture in all its complexity.

“An intimate family history, an anguished love letter to an ancient and broken homeland, and a spirited defense of journalism and truth at a time when both are under attack almost everywhere.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Unspool[s] his tale in such a way that you feel like you just sat next to the most interesting guy in the bar . . . a primer on Iran, American politics, journalism, and hope.” —W. Kamau Bell

“Prisoner is Rezaian’s story of his arrest, imprisonment, trial and eventual release . . . It’s also a revealing account of his childhood, family and marriage. Perhaps mirroring how he was left to his thoughts in prison, the narrative is digressive, jumping back and forth to different periods of his life. And it works . . . Rezaian is unsparingly intimate throughout.” —NPR.org

In July 2014, Washington Post Tehran bureau chief Jason Rezaian was arrested by Iranian police, accused of spying for America. The charges were absurd. Rezaian’s reporting was a mix of human interest stories and political analysis. He had even served as a guide for Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown. Initially, Rezaian thought the whole thing was a terrible misunderstanding, but things grew dire as it became an eighteen-month prison stint with impossibly high diplomatic stakes.

Rezaian had tireless advocates working on his behalf. His brother lobbied political heavyweights including John Kerry and Barack Obama and started a social media campaign—#FreeJason—while Jason’s wife navigated the red tape of the Iranian security apparatus, all while the courts used Rezaian as a bargaining chip in negotiations for the Iran nuclear deal.

In Prisoner, Rezaian writes of his exhausting interrogations and farcical trial. He also reflects on his idyllic childhood in Northern California and his bond with his Iranian father, a rug merchant; how his teacher Christopher Hitchens inspired him to pursue journalism; and his life-changing decision to move to Tehran, where his career took off and he met his wife. Written with wit, humor, and grace, Prisoner brings to life a fascinating, maddening culture in all its complexity.

“An intimate family history, an anguished love letter to an ancient and broken homeland, and a spirited defense of journalism and truth at a time when both are under attack almost everywhere.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Unspool[s] his tale in such a way that you feel like you just sat next to the most interesting guy in the bar . . . a primer on Iran, American politics, journalism, and hope.” —W. Kamau Bell

“Prisoner is Rezaian’s story of his arrest, imprisonment, trial and eventual release . . . It’s also a revealing account of his childhood, family and marriage. Perhaps mirroring how he was left to his thoughts in prison, the narrative is digressive, jumping back and forth to different periods of his life. And it works . . . Rezaian is unsparingly intimate throughout.” —NPR.org

BUY NOW FROM

COMMUNITY REVIEWS